Nearly every time I go out for a morning run, I see a double-decker bus jammed full of tourists with fancy cameras. And then I have to stop and let them take my photo and it’s totally embarrassing.

No, that last part is not true.

The bus full of tourists part, however, is real. And it got me wondering, what in the heck are they looking at?

I already knew this central Palm Springs neighborhood is home to swanky digs and architectural gems. And I knew celebrities and Hollywood legends made this area their playground. I just didn’t exactly where, who or what.

So I did some googling and came up with a list of addresses. (This Southern California hiking site was a tremendous resource. Thanks!) Then I grabbed my iPhone for some jogging and shooting.

This is not a comprehensive list by any means. They’re just some of the fun celeb homes I run past every day. (OK, OK. Three times a week.) And I still have at least a dozen more to photograph. So stay tuned for part 2!

Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell • 550 Via Lola

This house is one of my favorites. Doesn’t it look so breezy and fun, just like the stars who lived there?

Debbie Reynolds • 670 Stevens Road

This house is perched on top of a tiny but steep hill. If you hold your computer up to your ear and listen hard enough, you might be able to hear me wheezing.

Elvis Presley • 845 Chino Canyon

Unattractive black fence. White rocks that look like the bubbles on a stagnant pond. CREEPY ELVIS FACE. What’s not to love?

Elvis and Priscilla Honeymoon Hideaway (WARNING: There’s music on that link) • 1350 Ladera Circle

I’ve heard a lot of people say this home is tacky, but I think it’s a charming, unapologetic throwback. Living here would be like having Tomorrowland in your living room.

Marilyn Monroe • 1326 Rose Ave.

This home wins the prize for the most difficult to photograph. It’s located surprisingly close to the street and isn’t gated or anything. But there’s SO MUCH SHRUBBERY. And I always seemed to be there when the sun was in the worst possible position. So excuse the weirdo color — but it just adds to the classic 1950s aesthetic, no?

Otherwise, it’s an adorable little home. I can easily imagine Marilyn padding around the yard in a silky robe with sexy bedhead.

Nat King Cole • 1258 Rose Ave.

Again, there’s a whole lotta landscaping goin’ on.

Ronald and Nancy Reagan • 369 Hermosa Place

Stately, conservative and totally California. I would expect no less.

Clark Gable • 222 Chino Dr.

Frankly my dear, I do give a damn. It’s just so pretty! And pink!

Sammy Davis Jr. • 444 Chino Dr.

The parties that must have gone down here. Can you imagine?

Cyd Charisse and Tony Martin • 1197 Monte Vista

Dean Martin • 1123 Monte Vista

Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy • 776 Mission Road

I didn’t want to run up to the gate and stick my phone through the fence to get a better photo. Especially since someone was home at the time. Just trust me, this house is everything you’d expect of Katharine the Great.

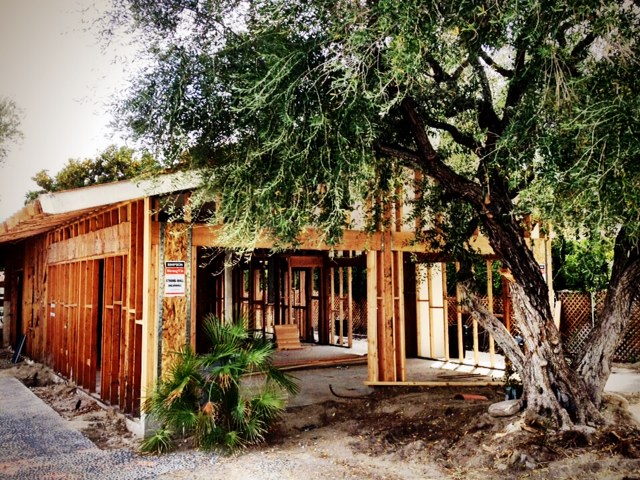

Sydney Sheldon • 425 Via Lola

Undergoing a second draft.

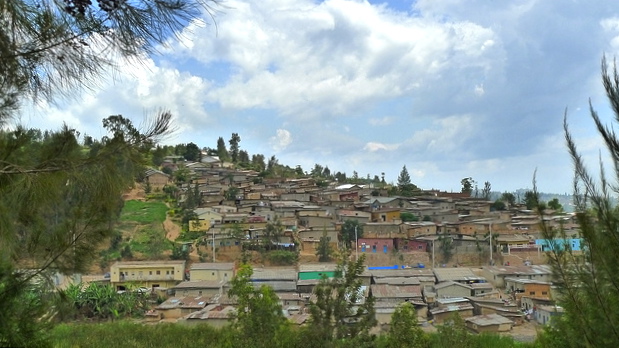

Howard Hughes • 335 Camino Norte

What? You can see the home of a famous recluse from the street?

NO! Of course not.

There’s actually a great big wall around this place, bigger than what you’d find at most prisons. But I jumped really high, held my phone up in the air and hoped for the best.

Liberace • 1441 N. Kaweah Road

I love this place. I mean, not for me. But it’s so … Liberace, all the way from the lion statues to the piano mailbox.

Coming soon: Jack Benney, Zsa Zsa, Frank, Bing and Lucy!