NOTE: Rwanda ended up being one of the highlights on my round-the-world trip. The first few days, however, were a little bumpy. This is the story of my first night in Kigali.

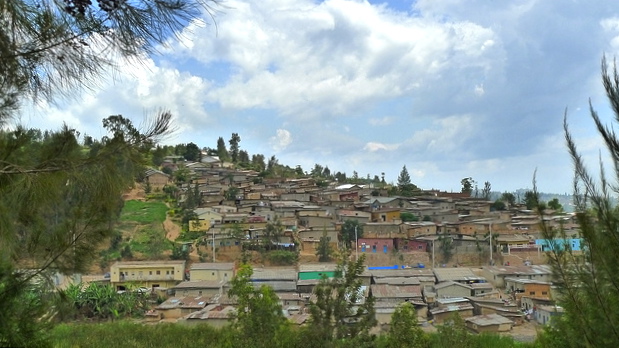

They call Rwanda “the land of 1,000 hills,” but I couldn’t see any of them from my room inside a prosthetic limb factory.

I was paying $35 a night for an excessively tall jail cell, fashioned from windowless walls that loomed cold and hard at least 25 feet high. The mosquito net above the bed looked like it had been vomited out by the ceiling. It sagged with knots on one side and was peppered with golfball-sized holes on the other.

A smaller stone wall partitioned off the bathroom, consisting of a shower head, a clogged drain, a wobbly sink and a toilet that didn’t flush. For an extra $10 a night, I could have received an “upgrade,” which meant that the owner would turn on the hot water, but my budget was too small to indulge in such luxuries.

I wasn’t even sure what I was doing in Rwanda, although it was easy enough to form a number of rationalizations. I had already spent a month in Uganda, and it was time to add another African country to the list. I was looking for a place to volunteer for a few weeks, and Rwanda sounded as good as anywhere else. And Rwanda is small and manageable, about the same size as Maryland.

Plus I really liked the movie, “Hotel Rwanda.” I imagined a land populated by 10 million Don Cheadles.

It helped that it was an incredibly simple border jump from Kampala, Uganda, to Kigali, Rwanda. The bus journey took just 8 hours — that’s lightning speed in African bus time — and cost only 25,000 Ugandan shillings — about $10. So what did I have to lose?

I arrived in Rwanda with no map, no plan and no idea where to stay. When the bus stopped at Kigali’s clogged and smelly Nyabugogo market, where every step involved a piece of garbage or rotting entrails, I simply hopped into a cab and asked the driver to take me someplace safe. And that is how I was steered to a prosthetic leg factory on the outskirts of town.

After I checked in, it was too late to travel 15 miles into the city but still too early to go to bed, so I explored the property instead. In the windows of my building, firestorms of sparks illuminated men in welding masks, constructing limbs for thousands of people who had been maimed during the 1994 genocide. On my way to the hostel bar, I stumbled over a stray fake leg.

The bar was reggae-themed, with portraits of Bob Marley sagging from mossy beams of wood. Steel-drum music blared from tinny speakers on top of the beer refrigerator. I perched on a leaning bar stool and ordered a Primus, the Budweiser of Rwandan beer.

“Primus for boys,” the bartender said, her face as flat and hard as a river stone.

“Um, that’s OK. I’ll take a Primus anyway,” I said.

“No.”

“Er, OK. Fine. I guess I’d like an Amstel?”

“No.”

“Are there any drinks I can have?”

“No. You already too drunk, lady,” the bartender said, matter-of-factly. “You don’t even know what you want to drink.”

With that, she dismissed me. This was my introduction to the incredibly frustrating task of communicating my desires in Rwanda, but it wouldn’t be the last. Only an hour later I would have the following exchange with the manager of the hostel/limb factory:

“Do you have a kitchen?”

“Oh, yes,” he said, smiling, but offering no follow-up.

“Is it a kitchen that guests can use?”

“Oh, yes,” he said, again with a wide grin.

“May I use the kitchen?”

“Oh, no.” With that, he walked away. No explanation.

Sober and hungry, I took deep yoga breaths to avoid punching anyone in the face. I grumbled to myself and kicked rocks all the way back to my room. There was a 4-month-old, smashed Bolivian granola bar in the bottom of my pack, so I ate that and threw curses at the blank wall of my cell. I paced the concrete floor like I was trapped inside a mental institution. I felt weak with an absence of power.

Just as my pity party was hitting its climax, the one lightbulb in the room gave up and went dark, as if it committed suicide.

I cried. I cried as the room remained frustratingly dark. I cried as mosquitos flew through my protective net and into my ears. I cried as the toilet spontaneously belched foul water onto the floor. Then I thought about how I had no real reason to cry in a land of genocide and unspeakable horror, and that made me cry harder. I cried for people I’d never known and the people I never would and all the ache in between.

That night I dreamt of malaria and detached body parts.

3 Comments

Did you ever find out what the miscommunications were?

Maggie, thank you, as ever. Following you is just the best. You inspire!

oh maggie, I so love reading about your adventures. You are such an amazing story teller and I can hardly wait until you write your book and share it with the world.