Tears dribbled into my oxygen mask, and that’s what I focused on, more than the dull tugging of surgical tools in my belly or the dry sandpaper in my throat. Just the tears sliding down my face, pooling under the plastic, becoming little clouds underneath the dome of the mask.

This wasn’t how it was supposed to be. I had a birth plan. My baby’s delivery was going to be natural. Drug-free. A blissful hippie love-fest. I wanted the lights to be dim, with faux flickering candles on the bedside table. I had lavender oil for relaxation. I made a special mix of music designed to inspire and encourage.

My hospital digs. Note the cassette player.

Everything went awry the day before, during what was supposed to be a routine OB appointment. The doctor hooked a belt to my belly and attached it to a machine, which spit out a long scroll of paper with jagged lines. The doctor ran her finger along the scroll and pointed to the dips in between the tall peaks, where the baby’s heartbeat looked erratic. Labor needed to be induced immediately, she said, and I cried. I desperately wanted my body to start labor the old-fashioned way — on its own — and I already felt like my baby’s birth was spinning out of my control.

At the hospital I was given a dose of Cytotec, a stomach ulcer drug that is also used to ripen the cervix for labor. It’s the same drug that I was given last year during my miscarriage, when my body refused to let go of the non-viable fetus.

Nurses also wanted to give me Pitocin, a synthetic form of a naturally occurring hormone, which induces strong contractions. I’ve read about the some of the adverse effects of Pitocin on newborns, so I wanted to hold off on that medicine unless it was absolutely necessary.

Hospital food.

In the movies, a woman in labor walks around and breathes heavily through the contractions. She stretches on a yoga ball or squats in a bathtub. She has the freedom of movement. That’s how I wanted it too.

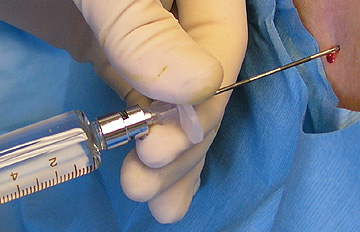

In reality, I was hooked to machines. There were two belts on my belly — one monitor for the baby’s heartbeat, one to measure my contractions. I had an IV of fluids, and a heartbeat monitor on my fingertip. A blood pressure cuff on my right arm inflated every 15 minutes. At some point, as night stretched into the long, bleary hours of early morning, a nurse strapped an oxygen mask to my face.

As the contractions came, I lay on the hospital bed and took every punch. Whenever I moved, the monitors slipped from my belly and the beeping from the machines grew loud and the nurses ran into the room and shifted my body into awkward positions and told me to be still. So I tried to quiet my body and imagined I was back at the ashram in India. I chanted with every blip on the monitor and pretended I was somewhere beyond the searing pain, even as my vision grew blurry and white along the edges.

I don’t remember what time it was when I asked for the epidural, only that I was too broken to continue.

“I can’t do this anymore,” I told my doula.

“You’re doing it,” she said.

“I’m tired of fighting,” I said.

I originally wanted to avoid the epidural, not so much because of the drug itself, but because I was scared of not feeling. I wanted to know when I was pushing. I wanted to experience my body presenting the baby to the world. And I think in a different situation I could have done without the epidural. But I walked into the hospital 16 hours earlier with an already listless spirit, and I couldn’t summon enough resolve to go on without help. The relief from the shot was almost immediate.

So that happened.

Everything was slow and lonely until it wasn’t anymore. Then everything moved very fast. The waves of contractions crashed quicker now, and the monitor on my belly displayed peaks like the Himalayas. Underneath my contractions, there was a canyon for every mountain — a dramatic dip of the baby’s heartbeat. As my contractions grew more powerful, his heartbeat decelerated for longer and more substantial periods. When his heartbeat slowed for more than two minutes, my doctor stood at the foot of my labor bed and said I needed to have an emergency Cesarean section. They prepared me for surgery.

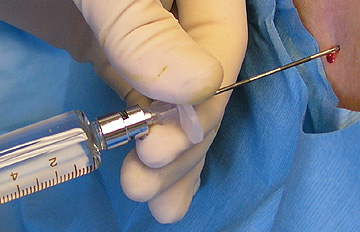

During pregnancy, I researched a lot of things about birth — but not once did I read anything about C-sections, because I wasn’t going to have one. So I was unprepared for the things that followed: The blue curtain draped a few inches from my face. The tables wheeled to each side of me, my arms stretched out and strapped down in a crucifixion pose. The peculiar feeling of having my belly split open and rearranged, as though I was a fish getting filleted.

My husband was seated next to my head, and he smoothed the hair back from my forehead. My throat was achingly dry, and my nose was stuffy. Tears rolled down my face and pooled inside the rim of my oxygen mask. “You’re doing great,” my husband said. “I’m so proud of you.” And then we heard a baby cry, bold and strong.

I’ve heard a lot of birth stories, and people always talk about the moment they saw their baby for the first time or the first touch of skin on skin. For me, I will always remember the brassy sound of my baby’s first cry, slicing through the cold, white air of the operating room. Robbed of all my other senses — hands strapped down, nose clogged, a curtain blocking my view — that noise was how I first connected with my child, and it was golden and it was perfect.

“It’s a boy!” one of the doctors shouted. “Ten fingers, ten toes!” said another. I cried, my husband cried, and my heart no longer fit inside of me.

Someone brought the baby to my head and laid him next to my face. I nuzzled him with my cheek, and I felt like an animal — a cat rubbing her kitten — before he was swept away to a recovery room. It would be another hour before I would touch Everest again.

Behind the curtain. (My husband took this photo, as my hands were still strapped to tables.)

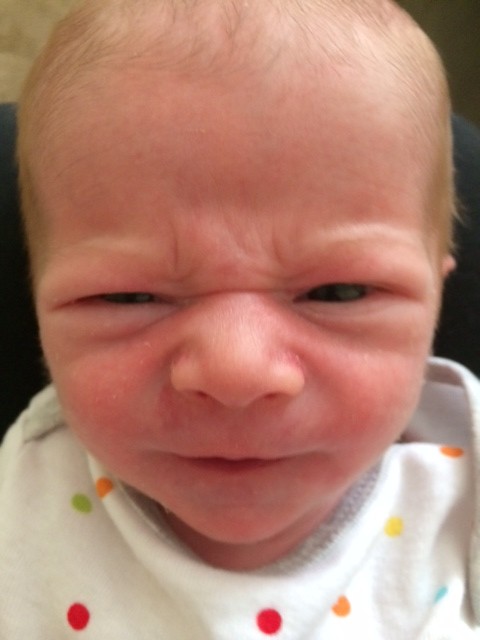

He came into the world so unexpectedly, the very opposite of my plan. No flickering candles, mood music, soothing smells; all bright lights, big noise, chaos and speed. But it was surprisingly perfect, an entrance that was totally Everest, just the way it was supposed to be.

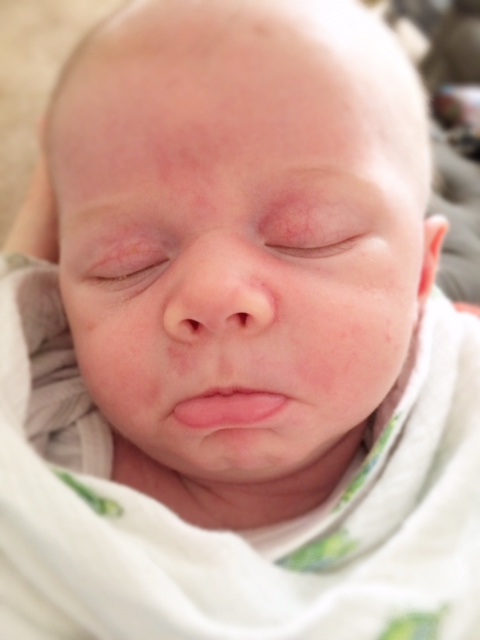

My guy.

Everest.