“I have walked that long road to freedom. I have tried not to falter; I have made missteps along the way. But I have discovered the secret that after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb. … I can rest only for a moment, for with freedom comes responsibilities, and I dare not linger, for my long walk is not yet ended.” — Nelson Mandela

There are two doors to enter the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, South Africa. One for whites. One for everybody else.

The rules aren’t enforced anymore, of course. Apartheid — the systematic racial segregation of South Africa — ended in 1994. But that’s the way it used to be. There were whites, and then there was everybody else.

And then came Nelson Mandela.

To be clear, I don’t know Mandela, and I am no expert in the politics of South Africa. I am simply someone who grew up watching the fall of apartheid on the news. Later, when I visited South Africa for the first time, I was moved by the fight for equality and efforts to move toward human dignity for all.

Out of everything from the anti-apartheid movement, I think I related most to Mandela because he was a troublemaker and I appreciate that in a person. I feel for the crazy ones, the misfits, the rebels — the whole Steve Jobs quote. I like all of that. And that was Mandela.

The name given to Mandela at birth, Rolihlahla, translates to “pulling the branch of the tree;” one who does not follow the established order. And Mandela certainly lived up to that name. It takes a certain kind of troublemaker to challenge authority, spend 27 years in prison, go on to become the first black South African president of your country and destroy decades of forced oppression.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, as Mandela is hospitalized in critical condition. His death is inevitable, but I hope we can keep some of the lessons from his life alive:

1. Lead by example.

While imprisoned, Mandela was restricted to a 6.5-foot by 8-foot cell with nothing but concrete floor and a bucket for waste. He was assigned to hard labor in a lime quarry. For much of that time, he was allowed just one letter every six months and one visitor per year for a half hour. Still, he walked tall and refused to show fear.

His fellow prisoners said just the act of watching Mandela walk through the courtyard, upright and proud, gave them the energy to go on.

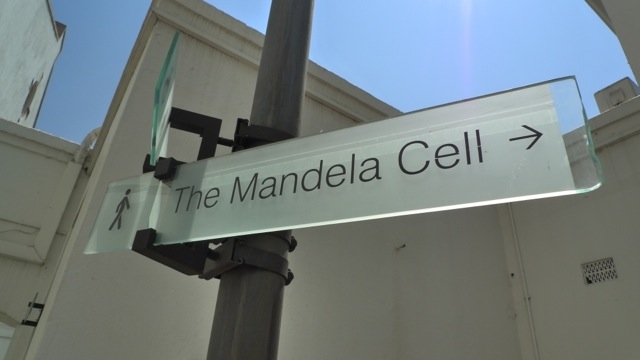

Sign pointing to the Mandela Cell at the Old Fort in Johannesburg. Mandela was only briefly held here. The majority of his imprisonment was on Robben Island in Table Bay.

2. Know that words have power.

During the 1970s, while he was imprisoned, Mandela wrote his memoir. Copies were wrapped in plastic containers and buried in the prison garden. It was hoped that another prisoner, due to be released soon, would smuggle it out. The containers were eventually discovered and Mandela was severely punished.

He continued to write anyway.

Knowing that words have such great impact, Mandela began to write more than his memoirs. The Old Fort in Johannesburg contains just a small sample of Mandela’s writings from his time on Robben Island — a total of 76 boxes in all. During his 27 years of imprisonment, Mandela sent more than 70,000 pieces of correspondence to prison authorities, lawyers and family. He frequently wrote on behalf of his fellow inmates, detailing issues about the quality of the food, protesting the regulations that banned books or filing complaints about improper care.

3. Value reconciliation over justice.

Mandela had every reason to hold grudges against his captors. Instead he worked toward reconciliation, which served as an example to a nation of wounded people.

As he wrote in “The Long Walk to Freedom”: “… the oppressor must be liberated just as surely as the oppressed. A man who takes away another man’s freedom is a prisoner of hatred, he is locked behind the bars of prejudice and narrow-mindedness. I am not truly free if I am taking away someone else’s freedom. Just as surely as I am not free when my freedom is taken from me. The oppressed and the oppressor alike are robbed of their community.”

Constitution Hill in Johannesburg serves as a visual example of this. The country’s highest Constitutional Court, which hears cases of human rights violations, now stands on the site of the Old Fort Prison, where freedom fighters were once held behind bars. Within the courtroom, a ribbon of glass serves as a symbol of the transparency of the proceedings.

Symbolic glass towers have been constructed atop the stairwells of the old prison on Constitution Hill.

4. Speak someone’s language.

This can be interpreted figuratively or, in Mandela’s case, literally. He spent many years learning and perfecting Afrikaans, the language of his oppressors. He realized that whatever solution might be found to apartheid would come from truly understanding one another.

As he once said, “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.”

5. Listen first, speak last.

Mandela grew up with the tribal tradition of consensus building, in which a leader listens first and speaks last, consolidating and integrating all of the views that have been expressed.

In “The Long Walk to Freedom,” Mandela writes, “Democracy meant all men were to be heard, and a decision was taken together as a people. Majority rule was a foreign notion. A minority was not to be crushed by a majority.”

Years later, Mandela used this technique as president. While members of his cabinet shouted at him, Mandela simply listened. When they were done and Mandela spoke, he summarized their thoughts before he deftly steered the conversation into the direction he wanted it to go.

“Lead from the back,” he said. “Let others believe they are in front.”

6. Spread knowledge.

In 2005, Mandela announced that his son, Makgatho, died of AIDS. Rather than keep quiet about the cause of death, Mandela said the disease should be given publicity so people will learn about it and stop being ashamed.

7. Learn about the experience of others.

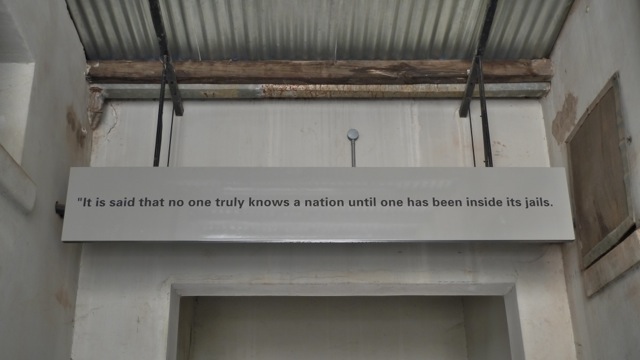

This might be my favorite Mandela quote, because it says so much about empathy.

Mandela quote on Constitution Hill, which once held jail cells and is now home to South Africa’s highest court.

8. Devote your life to something worth dying for.

Mandela was so committed to equality of all people that he said of his fight, “It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

9. Realize work is not accomplished alone.

Mandela wasn’t the only person who fought apartheid — he is just one of many who believed in the dignity of all. There were decades of uprisings and protests. Many people sacrificed their lives, including hundreds of schoolchildren.

At the exit of the Apartheid Museum, there is a bridge that passes through two piles of rocks. On the right side is a small pile. On the left side, the pile is enormous. As each visitor leaves, they are asked to move a rock from the right side to the left.

The big stack of rocks is what people, together, have already accomplished. It demonstrates how one small thing, done by many people, can move mountains.

As Mandela said, “It always seems impossible until it’s done.”