“When you realize the value of all life, you dwell less on what is past and concentrate more on the preservation of the future.” — Dian Fossey, Gorillas in the Mist

Dear Everest,

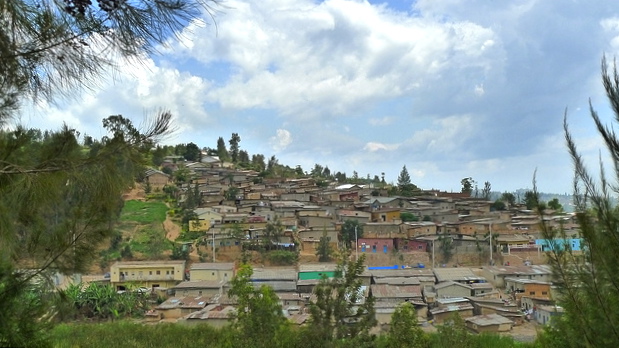

Once, on drizzly Rwandan morning when the Virungas were swathed with mist as fine as cotton candy, I hiked into the mountains to follow a family of mountain gorillas. To get there, I sliced through tangles of vines and branches with a long, solid machete. When the mountain got particularly steep and slippery, I used the machete to carve steps into the mud. Finally, after a few hours and a lot of sweat, I reached the gorillas.

They were remarkable. Truly. Gorillas aren’t aggressive unless threatened, and I think this group knew they were among friends. The silverback walked past me and put his enormous hand on my shoulder before moving on. He paused at the edge of a clearing and surveyed the landscape.

There were other adult gorillas. Some male, some female, although I didn’t really know how to tell the difference. They were gentle and kind. And there were babies, joyful baby gorillas, who plucked ripe berries from the bushes, scratched their heads, and awkwardly tried to swing from one tree to another.

I watched as the gorillas nurtured their young, the babies riding on their mothers’ backs or nestled in the crook of an arm.

One of the adult gorillas flattened some of the foliage into a nest and placed her baby there to rest. When the baby was good and comfortable, the mama perched nearby where she could keep watch. They were so much like humans.

Even so, I remember thinking, “Nope. Not me.” I didn’t think I could ever care for a child in that way. I didn’t have that capacity for selflessness, and when I searched within myself, I found zero maternal instinct. I was a woman who wielded a machete in the mountains, after all, not the type to nurture anyone.

Even when you arrived, I was unsure about this arrangement. I spent the first few months struggling to figure out how to make room in my life for a baby. Your bassinet was shoved between my bed and my nightstand, and it always felt like I was trying to wedge you into someplace you didn’t belong. Someone said to me, “I guess you’re done traveling now,” and I wondered if that was true, if my world was shrunken and small now.

But somewhere along the way, my world didn’t just stretch to accommodate you — you completely expanded it.

In fact, I suspect now that everything I’ve ever experienced, every skydive and every sunset, every place I’ve ever been, every trail I’ve ever walked, it was all leading me to you. And everything I have yet to experience, it already seems bigger and brighter because I’ll be experiencing it for two.

I get it now, this primal drive to care for another being. All I want to do is build a nest for you, a place to keep you safe and warm while I stand watch. We are a family.

Love, Mama